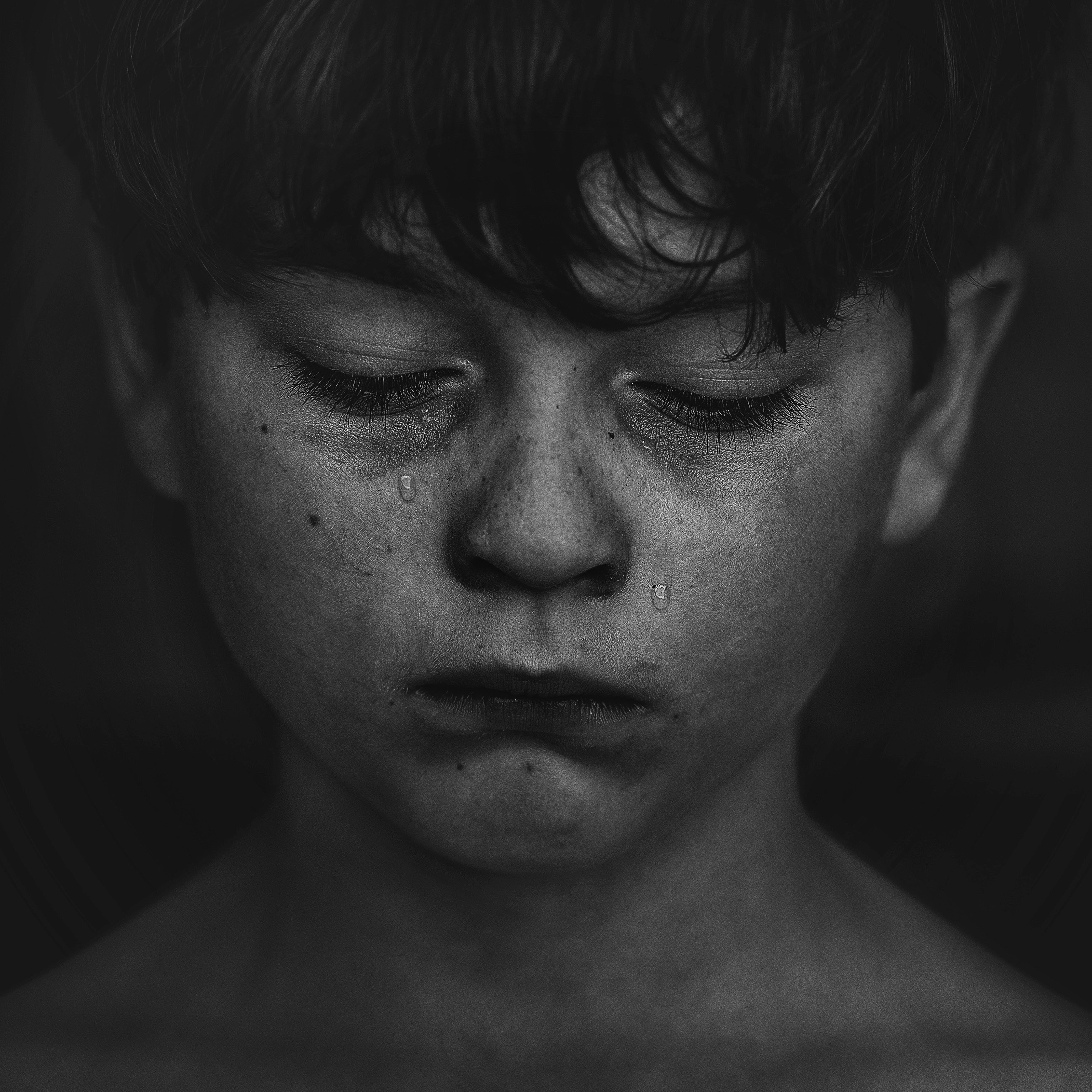

From the moment we are born, we cry. It is our announcement to the world that we have arrived. That we are alive. And it is rejoiced.

But no one lets a baby cry for too long. Not even when their cries mark a moment to be celebrated. A baby’s cries are muted by the gentle rocking of another human being, the warmth of skin to skin contact, perhaps while feeding at their mother’s breast. Soon, the cries are soothed.

At first, without words to express hunger or tiredness or discomfort, a parent intimately comes to know the different cries, perhaps indiscernible to others. Every effort is made to calm the tears – signs of distress – as soon as possible. This is why adhering to the “let your child cry himself to sleep” approach is so difficult, if not impossible for most, because it goes against our instincts.

As the baby grows into a child, parents become even more tuned into which cries are ‘real’ versus those that are seen as being manipulative – “crocodile tears” as some call those that don’t appear genuine. Parents and other adults determine which require soothing versus ignoring for fear of giving them too much attention and therefore encouraging more of the same. Yes, tears can be incredibly powerful and we grow up recognizing this by the way in which we are responded to when we cry.

Why, then, I wonder, if tears are typically responded to with tenderness, do the majority of my clients apologize for their tears? And why are they apologizing to me? Because they don’t want to inconvenience me or cause me any discomfort? To the invisible figures in the room who may have, over the years, shamed them into believing that tears are a sign of weakness? Led them to believe that their tears, once seen as pure and important, are no longer acceptable?

And if they have been shamed or taught to stifle their tears, at what age did this begin?

Was it when they were ten years old and crying after falling off their bicycle to hear their parent say “stop crying like a baby. It’s only a little scratch?” Was it after being asked “what are you crying about now?” in a tone that suggested that expressing oneself through tears was not okay. Was it learnt by watching a stoic parent, wanting to show “strength,” after the family pet had died? Or because he was told that boys don’t cry.

I was most struck by the degree to which we apologize for crying when at the funeral of a dear family friend recently. Her son in law appeared composed at first, but as he continued to deliver his heartfelt eulogy about a mother in law “like no other,” his sobs became more audible. He apologized over and over to the people listening but they too were crying too hard to give it a second thought. Later, after the burial had taken place, I approached him to share how touching his words were and how moved I was. Again, he apologized and said that he felt that his tears had gotten in the way, I’m not sure how convincing I was about how his tears, in fact, were part of why everyone was so moved. He had not only expressed how he felt towards her in words but through raw, palpable emotion. Emotion that one would surely expect to feel and show at a funeral of all places. And yet, despite this, there he was – apologizing for what is so normal. So natural. So real.

So too are the tears that my clients shed on what I call my “crying couches”. The tears I welcome in anticipation of my clients feeling relief at releasing their emotions in a safe place. And yet, despite offering a safe and supportive environment in which to express vulnerability, to show weakness (if that is what they have been taught tears represent), nine out of ten clients say “I’m sorry” at the first sign of tears and want reassurance that there are no tell-tale signs of crying on their faces before they emerge from my office.

I tell them that I encourage tears. That I’m honoured to be present. That tears are good. That they release toxins that are best gotten rid of. I offer them a box of tissues while letting them know that it’s okay to cry as much or for as long as they need to. I reassure them that despite their fears, that yes, they will be able to stop once they start.

And I hope that my words resonate with them. That they reassure them that no matter their gender, their culture, their age, to celebrate and embrace their tears and to not apologize for being human.